Nightmare in No Man's Land

9th June 1916

The aim of this series of TOMMIES is to build towards incidents that occur on the 30th June 1916, the day before the First Day of the Battle of the Somme.

When I started thinking about TOMMIES back in 2009 I always wanted to have episodes that weren't based on actual "battle-fighting" days, and this series is a perfect example. It wasn't the soldier's experience to be fighting every day for four and a half years, so it shouldn't be that experience for the real-time listener.

So the fixed date for the series was always 30th June. TOMMIES is a weekly drama. So when the dates presented themselves working backwards through June I didn't know what incidents would present themselves.

As always, it was a piece of dramatic connection between two truths that made the episode for me. The first was to be found in the War Diary for 9th June 1916 of the 179th Tunnelling Company at La Boisselle. They were scheduled to blow two camouflets at 1115. As I understand it, these are special underground mines designed to collapse enemy tunnels by sending a pressure wave through the very earth.

The second was a remarkable passage in a book I've mentioned many times, THE WAR THE INFANTRY KNEW by Dr Dunn of the 2nd RWF, pp210-212. It concerns the partial burying alive of men on patrol in NML led by Captain H Blair.

Blair was buried from the neck down. Just like Mickey, he was scared upon the approach of a German patrol that his protruding head would be kicked like a rotten turnip. His troops became delirious. He tried to build, tiny spot of mud by tiny spot of mud, an indistinguishable defensive wall between him and the enemy, but it was knocked down by unaimed machine gun fire.

So these two ideas seemed to want to go together. Mickey is stuck out in NML, with the camouflets about to go off.

Who could be there with him?

Vasserot we'd met in the previous episode, and we know well enough how Mickey would be interested in the parleur set. Designed to send signals through the earth from copper stake on a Morse-key style transmitter to copper stake on a receiving set, this seems a remarkable idea. But a godsend: it doesn't matter how churned up the earth of NML is, the signal always gets through.

Demanjit Singh was based on the Sikh Risildars (cavalry lieutenants) attached to Skinner's Horse. Their War Diary tells us they were sent to the front to help with digging communication trenches for the big attack. They surely felt they should have been practising on their horses for the attack instead, but they were posted to Mesopotamia within a few days after this episode so perhaps that was what was behind that thinking.

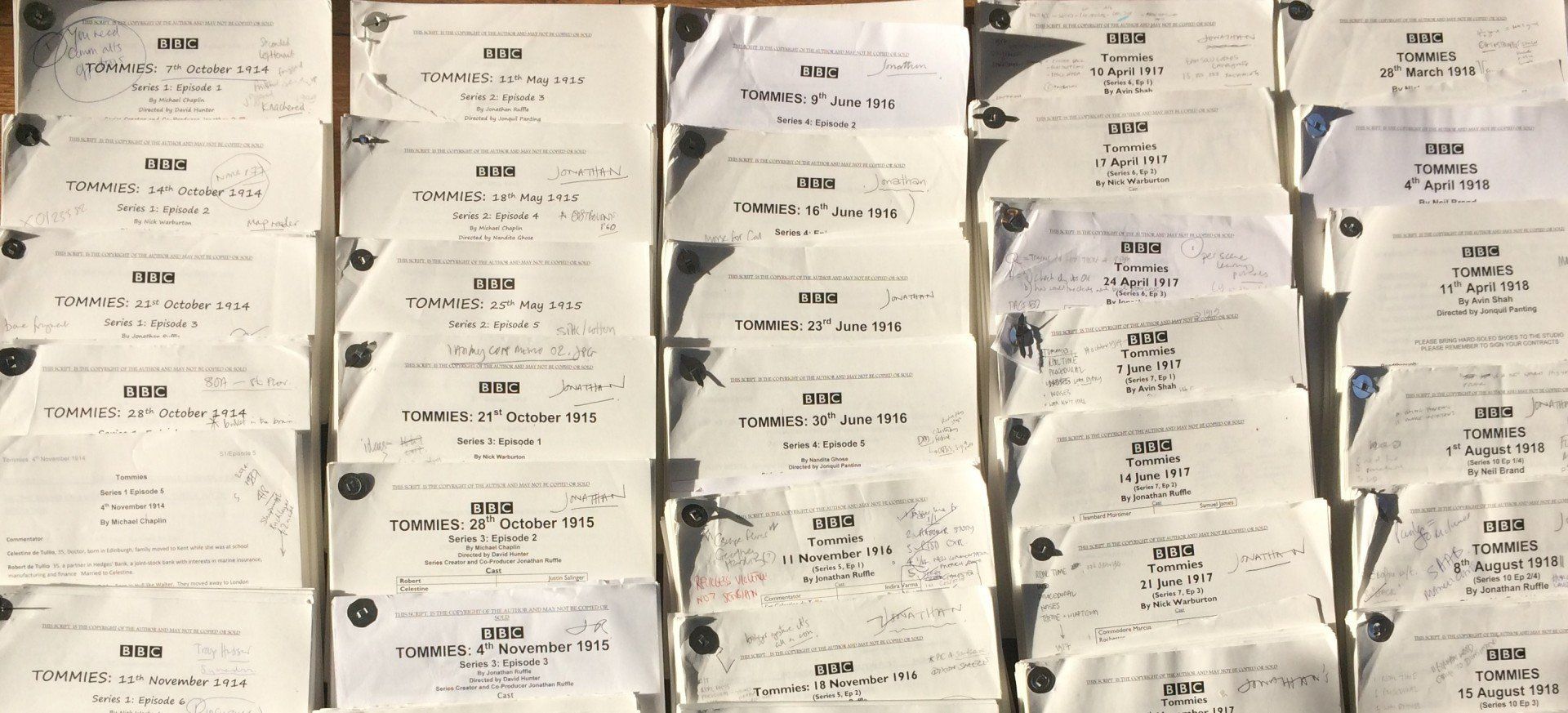

Quick camera-phone film:

I was keen we should explore the notions prevalent at the time about troop's willingness to fire at and kill enemy soldiers. It was a bit tricky to map how to say this as we train our soldiers in a completely different way now, so there was a distinct possibility the 2016 audience would just find this material so unlikely they'd reject it.

But Vasserot is quoting research known in every French military academy since the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, written down by Major Ardant du Picq in a training manual best-seller. He contended troops would not shoot to kill another human being, particularly the kind of happy civilian volunteer that makes up the Tyneside pals battalions.

I blended in latter research from SLA Marshall who looked at kill ratios in the Pacific in WW2. He found 80-85% of men will not shoot at another man, so ingrained is the moral and instinctual desire not to harm another human being. Being in a mass of troops all firing disguises this behaviour, and most get away with it. About 15% will kill, and they are likely to be following the lead of the 2% of the insanely brave or psychopaths who actually enjoy it.

Later writers – Richard Holmes among them – point out that even at Rorkes' Drift (the film ZULU), men used thirteen bullets to kill one Zulu, and those were terrified soldiers facing death at the point of a spear. And for a WW1 example, the East Surreys at Mons had to be kicked by their officer to make them aim low.

As I said before, soldiers are now trained to shoot to kill in far more effective ways and these figures no longer apply. But it seemed a fresh perspective we couldn't miss: otherwise we have an image of men running around with bayonets at sacks with screaming red-faced drill sergeants.

As always, something that got left out, and once again, something from the excellent TYNESIDE IRISH by John Sheen: the miners in the Tyneside battalions often tied their identity tags to their braces, just like they had done with their colliery tokens down the mine. When the burial parties found bodies, they only had time to feel around the corpse's neck, and rarely searched anywhere else. For this reason, many Tynesiders were buried as unknown in CWGC cemeteries.