We'll always have Paris

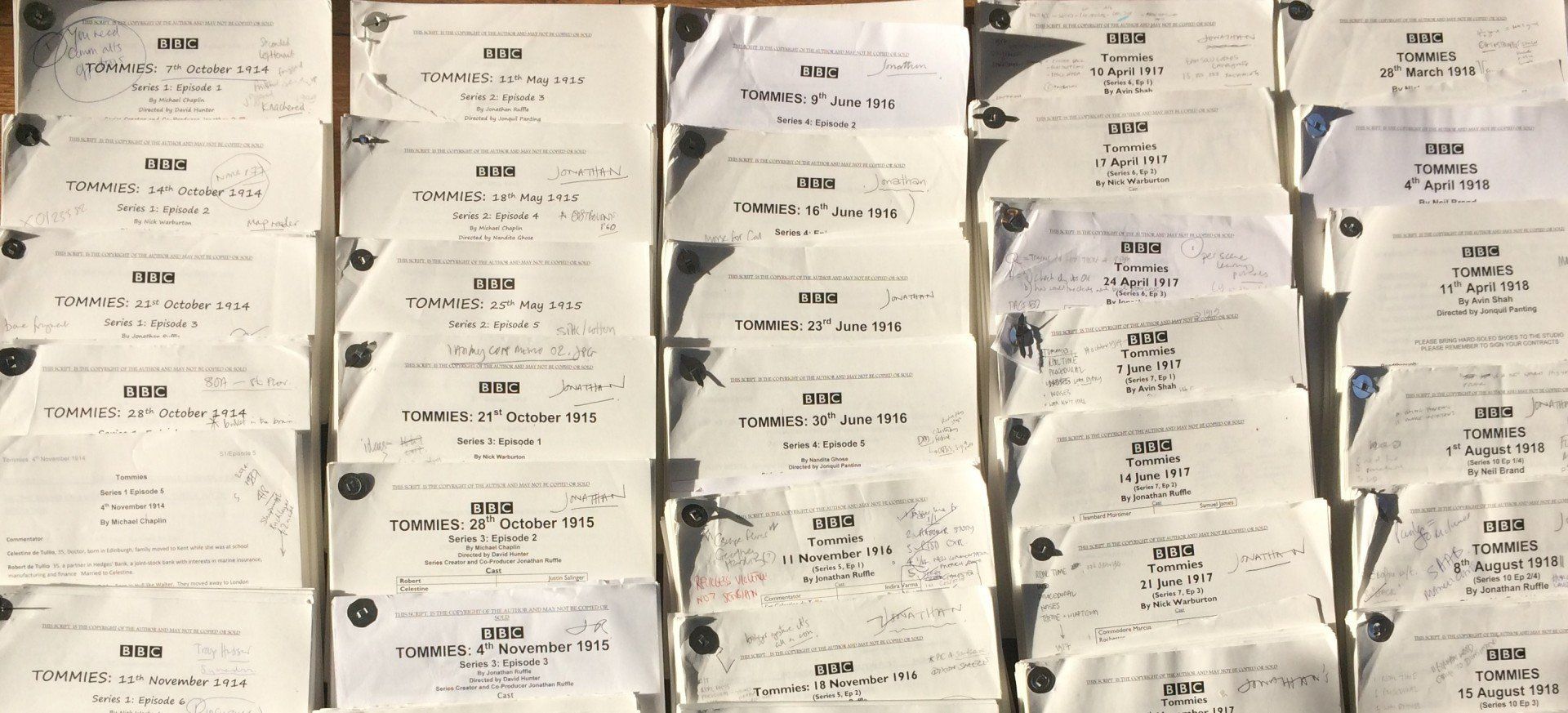

16th June 1916

16th June 1916

How much truth can you ever really get from the signals that people give you? That was the question asked by this episode.

It was truly exciting to write. The whole Allied intel set-up in Paris was such a factually rich and unexpected place to set a drama, I had to throw out far more material than I was able to include. I'll try to suggest where there is more as I go.

The Eiffel Tower was genuinely used in French long range wireless direction finding, (The FRENCH SECRET SERVICE by Douglas Porch was helpful here) and the Director of Army Signals archives show the British had their time signal generator up there from about September 1914. We had an interesting production point about the number and the nature of the pips. It's a BBC rule that if you want to use the pips in a broadcast you can so long as you don't use the 'five plus one long one'. I'm afraid I took my eye off the ball here and in my keenness to use less pips I never researched when the long pip was introduced. Well, several correspondents - Sean Maffett, I'm talking to you here - have pointed out that it is within living memory that all pips were the same length. So, I suspect we got this one wrong.

The Bureau Central Interallié in the Boulevard St Germain actually existed and was structured in exactly the way I wrote it, opposite the Ministere de la Guerre. The main source for this was A PICTURE OF A LIFE by Lord Mersey, one of the cheifs of the operation. He is good on both structure and detail: it is his story about Lilian Douglas-Pennant, the wife of a General who worked there, that gave rise to the "Sonnez la Generale" moment.

Mickey's input into direction finding and the intel to be interpreted from code changes comes substantially from THE BRITISH ARMY AND SIGNALS INTELLIGENCE by John Ferris, and documents in the TNA.

Miss Softley and Mrs Flinders were based on several women working in Paris at this time, or just a few months later. It was a Miss Hannam who knew French and German and had served in France at GHQ on German field codes, and a Miss Haylar who worked on current Italian non-alphabetical codes. These turned up in several sources, but the detail was in INSIDE ROOM 40 by Gannon, and FEMALE INTELLIGENCE: WOMEN AND ESPIONAGE IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR by Tammy M. Proctor.

I had been educated by the Enigma story to expect mathematicians, rather than linguists. But number-crunchers were required in WW2 because the Intel was encoded using machines using mathematical principles and needed the early maths of computing to break it. That is not the case here - these are word-based codes encoded by humans not machines. A deep understanding of linguistics was easily the most important thing.

However, WW1 lady mathematicians were used in the armaments industry: KARL PEARSON AND COMPUTING FOR THE MINISTRY OF MUNITIONS by June Barrow-Green gives more details.

But a real find was courtesy the Military Intelligence Museum Archive on the Army base at Chicksands. I was given access by archivist Joyce Hutton to the Fisher nee Bosworth papers.

Charlotte Fisher joined the BCI in 1916 and it was quite something to hold her Ministere de la Guerre pass for 1917: Miss Charlotte Bosworth, number 36, signed Chef du Service Interieur. It was Charlotte and subsequently her sister Sylvia who pioneered the use of German soldier's paybooks as a form of statistical breakdown of their losses.

Other intel sources consulted included Jim Beach's brilliant HAIG's INTELLIGENCE, THE QUEST FOR C by Alan Judd, THE DEFENCE OF THE REALM (MI5) by Christopher Andrew and The SECRET HISTORY OF MI6 by Keith Jeffrey.

Celestine is firmly rooted in the life of Flora Sandes. Her original works are at archive.org and in the IWM library, but a recent biog A FINE BROTHER by Louise Miller makes her life much easier to follow. The positions of her division on this day are derived from FROM SERBIA TO JUGOSLAVIA by Gordon Gordon-Smith.

It was truly exciting to write. The whole Allied intel set-up in Paris was such a factually rich and unexpected place to set a drama, I had to throw out far more material than I was able to include. I'll try to suggest where there is more as I go.

The Eiffel Tower was genuinely used in French long range wireless direction finding, (The FRENCH SECRET SERVICE by Douglas Porch was helpful here) and the Director of Army Signals archives show the British had their time signal generator up there from about September 1914. We had an interesting production point about the number and the nature of the pips. It's a BBC rule that if you want to use the pips in a broadcast you can so long as you don't use the 'five plus one long one'. I'm afraid I took my eye off the ball here and in my keenness to use less pips I never researched when the long pip was introduced. Well, several correspondents - Sean Maffett, I'm talking to you here - have pointed out that it is within living memory that all pips were the same length. So, I suspect we got this one wrong.

The Bureau Central Interallié in the Boulevard St Germain actually existed and was structured in exactly the way I wrote it, opposite the Ministere de la Guerre. The main source for this was A PICTURE OF A LIFE by Lord Mersey, one of the cheifs of the operation. He is good on both structure and detail: it is his story about Lilian Douglas-Pennant, the wife of a General who worked there, that gave rise to the "Sonnez la Generale" moment.

Mickey's input into direction finding and the intel to be interpreted from code changes comes substantially from THE BRITISH ARMY AND SIGNALS INTELLIGENCE by John Ferris, and documents in the TNA.

Miss Softley and Mrs Flinders were based on several women working in Paris at this time, or just a few months later. It was a Miss Hannam who knew French and German and had served in France at GHQ on German field codes, and a Miss Haylar who worked on current Italian non-alphabetical codes. These turned up in several sources, but the detail was in INSIDE ROOM 40 by Gannon, and FEMALE INTELLIGENCE: WOMEN AND ESPIONAGE IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR by Tammy M. Proctor.

I had been educated by the Enigma story to expect mathematicians, rather than linguists. But number-crunchers were required in WW2 because the Intel was encoded using machines using mathematical principles and needed the early maths of computing to break it. That is not the case here - these are word-based codes encoded by humans not machines. A deep understanding of linguistics was easily the most important thing.

However, WW1 lady mathematicians were used in the armaments industry: KARL PEARSON AND COMPUTING FOR THE MINISTRY OF MUNITIONS by June Barrow-Green gives more details.

But a real find was courtesy the Military Intelligence Museum Archive on the Army base at Chicksands. I was given access by archivist Joyce Hutton to the Fisher nee Bosworth papers.

Charlotte Fisher joined the BCI in 1916 and it was quite something to hold her Ministere de la Guerre pass for 1917: Miss Charlotte Bosworth, number 36, signed Chef du Service Interieur. It was Charlotte and subsequently her sister Sylvia who pioneered the use of German soldier's paybooks as a form of statistical breakdown of their losses.

Other intel sources consulted included Jim Beach's brilliant HAIG's INTELLIGENCE, THE QUEST FOR C by Alan Judd, THE DEFENCE OF THE REALM (MI5) by Christopher Andrew and The SECRET HISTORY OF MI6 by Keith Jeffrey.

Celestine is firmly rooted in the life of Flora Sandes. Her original works are at archive.org and in the IWM library, but a recent biog A FINE BROTHER by Louise Miller makes her life much easier to follow. The positions of her division on this day are derived from FROM SERBIA TO JUGOSLAVIA by Gordon Gordon-Smith.

Related Episodes

Related Episodes