The Last Day of the Battle of the Somme

18th November 1916

18th November 1916

True to form the world's media flickered briefly to life to recognise the Last Day of the Battle of the Somme, no doubt due to the extraordinary efforts of the CWGC at Thiepval, commemorating every single one of the 141 days of the Battle.

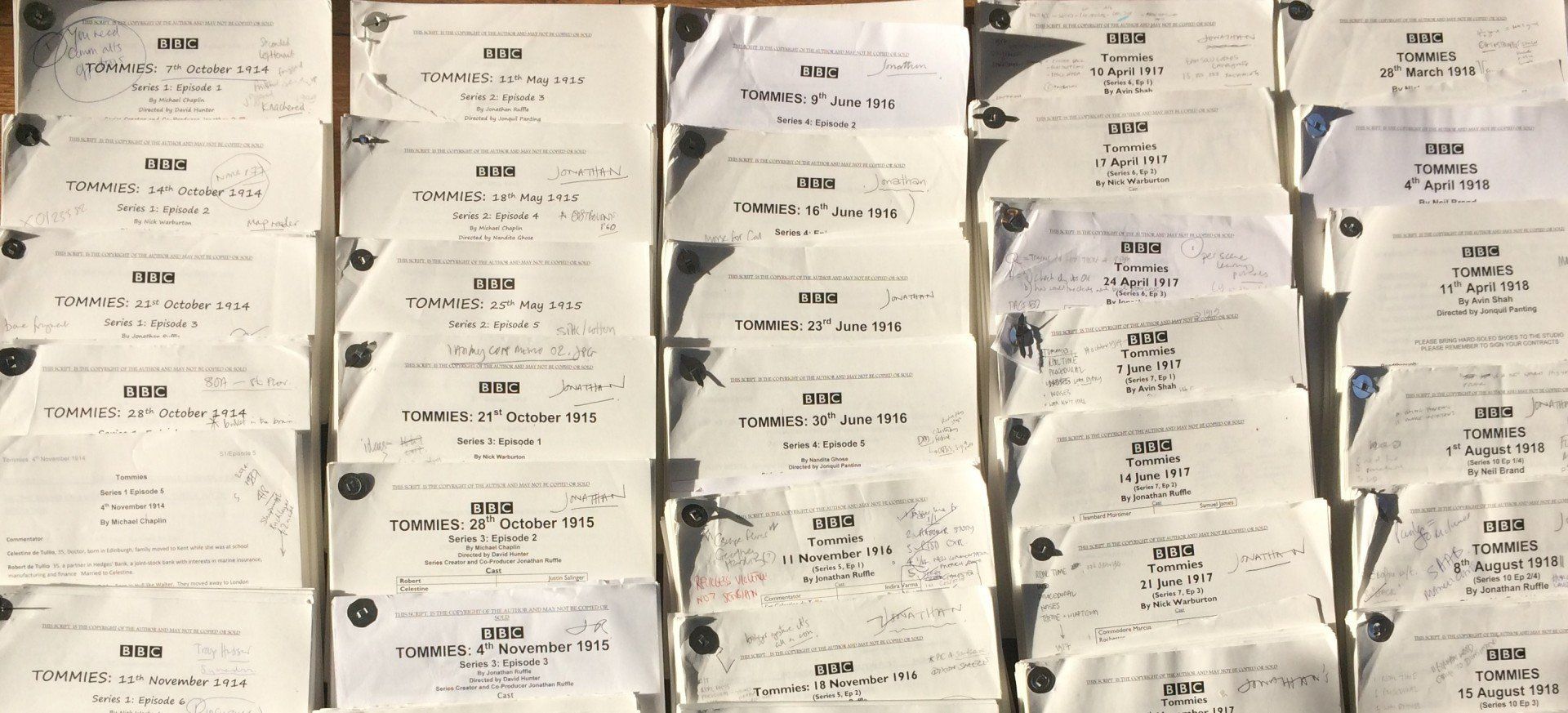

There had been, of course, a plethora of programmes about the First Day of the Battle of the Somme. TOMMIES asks how such a battle ends...

18th November 1916

True to form the world's media flickered briefly to life to recognise the Last Day of the Battle of the Somme, no doubt due to the extraordinary efforts of the CWGC at Thiepval, commemorating every single one of the 141 days of the Battle.

There had been, of course, a plethora of programmes about the First Day of the Battle of the Somme. TOMMIES asks how such a battle ends...

There had been, of course, a plethora of programmes about the First Day of the Battle of the Somme. TOMMIES asks how such a battle ends...

Who orders men into action on the Last Day of the Battle of the Somme, 18 November 1916? Who plans to expend lives on one more day of battle, rather than stopping yesterday or attacking tomorrow? What possible gain could there be after 140 days fighting on the Somme? Late battles in any campaign have a quality both nightmarish and abstract, random yet inevitable.

What follows are some of my original notes about this day in TOMMIES terms.

Mickey has fresh signal challenges, some showing how much the Signals have learned over the gruelling summer and autumn. The Somme was a dramatic learning curve for the British Army, a story almost completely lost to history. He also has brand new problems -- particularly those associated with the newfangled tank and the unprecedented signals art of sound-ranging, the ability to find an enemy gun just by listening to it.

With hindsight we can only see the Somme as a battle with a terrible start and a drawn out struggle for a few miles of churned up mud. Haig and his advisers saw it differently. They sucked up the first day, but also read in their intelligence reports that the German Army had been dealt a blow. In a few more days, they might collapse completely. The summer and autumn of 1916 is littered with as many successes -- and optimistic assessments of those successes -- as would break the stoutest heart. For example, they saw endless reports showing that new and inexperienced German soldiers were being put straight into the line (Miss Softley at the BCI supplying some of it), and saw this as the bottom of the barrel being given its final scraping. This was true, and often the British attacked strongpoints held by a paper-thin force ridiculously close to breaking. Haig may have seen he was not advancing much further than his objectives all those months ago on 1st July, but if the enemy wanted to throw his last few children at him where he stood, why should he mind?

The British attack on the Somme had finally forced the Germans to give up attacking Verdun, had made them forget their own planned 1916 attacks on the Somme and at Arras, and pray for winter to arrive so the two exhausted and bloodied boxers could stop hanging on and begging for it all to end. The Somme had been such a disaster for the Germans they wanted to pull back to a newer and more fortified position -- the Hindenburg line. They'd made this decision in early September, whereas the Somme battle ran on for a further two months. Raiding enemy trenches (which we and the Tommies can understandably see as pointlessly belligerent and a willy-waving practice by middle-ranking officers) often brought back valuable confirmatory Intel, probably justifying the practice.

What follows are some of my original notes about this day in TOMMIES terms.

Mickey has fresh signal challenges, some showing how much the Signals have learned over the gruelling summer and autumn. The Somme was a dramatic learning curve for the British Army, a story almost completely lost to history. He also has brand new problems -- particularly those associated with the newfangled tank and the unprecedented signals art of sound-ranging, the ability to find an enemy gun just by listening to it.

With hindsight we can only see the Somme as a battle with a terrible start and a drawn out struggle for a few miles of churned up mud. Haig and his advisers saw it differently. They sucked up the first day, but also read in their intelligence reports that the German Army had been dealt a blow. In a few more days, they might collapse completely. The summer and autumn of 1916 is littered with as many successes -- and optimistic assessments of those successes -- as would break the stoutest heart. For example, they saw endless reports showing that new and inexperienced German soldiers were being put straight into the line (Miss Softley at the BCI supplying some of it), and saw this as the bottom of the barrel being given its final scraping. This was true, and often the British attacked strongpoints held by a paper-thin force ridiculously close to breaking. Haig may have seen he was not advancing much further than his objectives all those months ago on 1st July, but if the enemy wanted to throw his last few children at him where he stood, why should he mind?

The British attack on the Somme had finally forced the Germans to give up attacking Verdun, had made them forget their own planned 1916 attacks on the Somme and at Arras, and pray for winter to arrive so the two exhausted and bloodied boxers could stop hanging on and begging for it all to end. The Somme had been such a disaster for the Germans they wanted to pull back to a newer and more fortified position -- the Hindenburg line. They'd made this decision in early September, whereas the Somme battle ran on for a further two months. Raiding enemy trenches (which we and the Tommies can understandably see as pointlessly belligerent and a willy-waving practice by middle-ranking officers) often brought back valuable confirmatory Intel, probably justifying the practice.

The Germans escaped their recruiting problems by a reorganisation of their entire army to rotate the right troops into the line. But a potential British breakthrough was a far more near-run thing that we might habitually think.

There had also been what we now refer to as a RMA, a revolution in military affairs. We are going to concentrate on the advances in signalling, but the British Army had learnt valuable lessons that it could only learn in the field: how to rehearse, authentically, and tell every man what's going to happen (what Mickey has been saying in series 4); strong top-down leadership; strong junior leadership -- devolving command; the encouragement of initiative; the use of the Mills bomb and small unit tactics; taking limited objectives with proper artillery support; the creeping barrage rather than an all-or-nothing bombardment; the retention of core groups of trainers within divisions; and to hell with local recruitment -- Pals -- it is efficiency that matters. These positive steps are good news for the Army, not so good if it is used as an argument to prolong the bloodbath.

The revolution in signalling affairs is on simpler lines. Among refinements to his normal bag of tricks, Mickey would now deploy a message thrower, capable of propelling the container of a message 800 yards. After the 30th June overhearing cock-up the Fullerphone was brought into general use. Kite balloons and aeroplanes were now being used to provide real-time observation using wireless to report, and tanks needed comms in three ways: first, communication between tanks and supporting infantry; second, communication between the tanks themselves; and third, communication between tanks and unit headquarters in the rear.

Signallers at all levels had experienced the difficulty of maintaining command and control during an attack.

One solution was almost too simple: moving Divisional HQ well forward at the outset of an attack. We know Mickey and Crowden advocated liaison officers in 1915 -- well, that has finally come on stream. Staff work -- the actual quality of orders sent -- was improved, as was speed of transmission from HQ to the front by dividing orders into preliminary and final so the activity ordered, what ever it was, could be started earlier.

There had also been what we now refer to as a RMA, a revolution in military affairs. We are going to concentrate on the advances in signalling, but the British Army had learnt valuable lessons that it could only learn in the field: how to rehearse, authentically, and tell every man what's going to happen (what Mickey has been saying in series 4); strong top-down leadership; strong junior leadership -- devolving command; the encouragement of initiative; the use of the Mills bomb and small unit tactics; taking limited objectives with proper artillery support; the creeping barrage rather than an all-or-nothing bombardment; the retention of core groups of trainers within divisions; and to hell with local recruitment -- Pals -- it is efficiency that matters. These positive steps are good news for the Army, not so good if it is used as an argument to prolong the bloodbath.

The revolution in signalling affairs is on simpler lines. Among refinements to his normal bag of tricks, Mickey would now deploy a message thrower, capable of propelling the container of a message 800 yards. After the 30th June overhearing cock-up the Fullerphone was brought into general use. Kite balloons and aeroplanes were now being used to provide real-time observation using wireless to report, and tanks needed comms in three ways: first, communication between tanks and supporting infantry; second, communication between the tanks themselves; and third, communication between tanks and unit headquarters in the rear.

Signallers at all levels had experienced the difficulty of maintaining command and control during an attack.

One solution was almost too simple: moving Divisional HQ well forward at the outset of an attack. We know Mickey and Crowden advocated liaison officers in 1915 -- well, that has finally come on stream. Staff work -- the actual quality of orders sent -- was improved, as was speed of transmission from HQ to the front by dividing orders into preliminary and final so the activity ordered, what ever it was, could be started earlier.

Another big problem. Before the Somme, there had been mobile, then static, warfare. Now it was a form best described as slow-moving siege warfare, neither one or the other, and almost impossible for signallers to plan for.

Let us now go through the events of the day, hanging the above on the skeleton where appropriate.

Certainly the intel picture was good. In an attack in the Beaumont Hamel area on 13 November, officers of four different German regiments were captured. This is a sign you are up against a hastily put-together hotch-potch, not a coherent unit.

The jumping off trenches for 57 Brigade were the same used on 1st July, ouch. One big difference was that the weight of shells fired to support the attack on a comparatively minute frontage was almost equal to that fired on the entire front on the First Day of the Battle of the Somme. The objective was the high ground near the village of Grandcourt, so the British would not have to spend the winter being overlooked.

Conditions were terrible: cold with sleet and snow. Cruelly, there had been a hard frost on the 16/17th November, making the ground passable. Since preliminary orders had gone out, a thaw set in. Men really did die of exhaustion trying to get out of the mud.

At 0045 the attack order was changed to take more of the village of Grandcourt. We are now sophisticated enough on TOMMIES to know a late order change suggests chaos behind the scenes rather than confidence and inspiration. This decision now seems curious. It was provoked by late afternoon aerial observations on the 17th by the RFC that the Germans had apparently abandoned their trenches at Grandcourt. Intel coming in from patrols by midnight indicated that those trenches were manned. And yet the attack still went in, with orders assuming the first state of affairs rather than the second.

Let us now go through the events of the day, hanging the above on the skeleton where appropriate.

Certainly the intel picture was good. In an attack in the Beaumont Hamel area on 13 November, officers of four different German regiments were captured. This is a sign you are up against a hastily put-together hotch-potch, not a coherent unit.

The jumping off trenches for 57 Brigade were the same used on 1st July, ouch. One big difference was that the weight of shells fired to support the attack on a comparatively minute frontage was almost equal to that fired on the entire front on the First Day of the Battle of the Somme. The objective was the high ground near the village of Grandcourt, so the British would not have to spend the winter being overlooked.

Conditions were terrible: cold with sleet and snow. Cruelly, there had been a hard frost on the 16/17th November, making the ground passable. Since preliminary orders had gone out, a thaw set in. Men really did die of exhaustion trying to get out of the mud.

At 0045 the attack order was changed to take more of the village of Grandcourt. We are now sophisticated enough on TOMMIES to know a late order change suggests chaos behind the scenes rather than confidence and inspiration. This decision now seems curious. It was provoked by late afternoon aerial observations on the 17th by the RFC that the Germans had apparently abandoned their trenches at Grandcourt. Intel coming in from patrols by midnight indicated that those trenches were manned. And yet the attack still went in, with orders assuming the first state of affairs rather than the second.

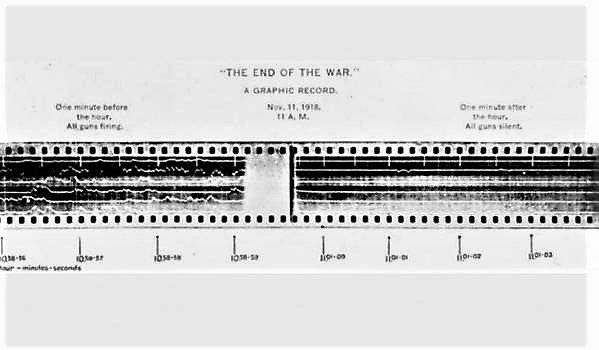

Tanks were to be used (recently used on the Somme to sporadic success), and sound-ranging to find and shell the enemy batteries (which relies on a suspended filament responding to pressure waves coming from distant guns: Heath Robinson-esque yes, but able to indicate not only range but calibre of the targeted gun. Developed by a signals officer who noticed a spider's web flutter in the faint blast, while sitting on an outhouse toilet).

The barrage and attack started at 0610 in the dark. The soldiers advanced as close to the creeping barrage as they could – this was an innovatory method of lifting a barrage by short 50 yard jumps or less to keep the Germans in their dugouts until the infantry, just behind the final shell, could attack. No more the dread walk towards the waiting Germans across No Man's Land. Unfortunately today the Germans have thought of their come-back to the creeping barrage: they have positioned their machine guns at the mapped furthest point of the barrage, and it is from there they now scythe down their attackers.

Even while the attack goes in, it is learnt that the operation has been strongly opposed at GHQ by the C.O, and though it has been ordered to go ahead, Haig wishes it to be known as a 'demonstration' rather than an attack, the classic way of reducing expectations in the hope of a lucky result.

57 Bde get into Grandcourt, excepting 8 North Staffords. They were one of WW1's many 'lost' battalions. Sounding slightly exotic, instead this is the drearily predictable fate of a battalion that fails to notice it hasn't mopped up a trenchful of Germans, goes past, and then find themselves cut off. 17 officers and 317 other ranks were lost.

The barrage and attack started at 0610 in the dark. The soldiers advanced as close to the creeping barrage as they could – this was an innovatory method of lifting a barrage by short 50 yard jumps or less to keep the Germans in their dugouts until the infantry, just behind the final shell, could attack. No more the dread walk towards the waiting Germans across No Man's Land. Unfortunately today the Germans have thought of their come-back to the creeping barrage: they have positioned their machine guns at the mapped furthest point of the barrage, and it is from there they now scythe down their attackers.

Even while the attack goes in, it is learnt that the operation has been strongly opposed at GHQ by the C.O, and though it has been ordered to go ahead, Haig wishes it to be known as a 'demonstration' rather than an attack, the classic way of reducing expectations in the hope of a lucky result.

57 Bde get into Grandcourt, excepting 8 North Staffords. They were one of WW1's many 'lost' battalions. Sounding slightly exotic, instead this is the drearily predictable fate of a battalion that fails to notice it hasn't mopped up a trenchful of Germans, goes past, and then find themselves cut off. 17 officers and 317 other ranks were lost.

No tanks even made it as far as the front line. All the hours of effort to coordinate them was rendered useless by mechanical failure.

In a story straight out of Mickey's 'Do Not Do This' file, having captured Grandcourt, 57 Brigade wander off, caught up in that strange lapse of concentration that affects combat units once they have taken their objective. But part of it is held and the British line will not be so dominated that winter.

A quick thank you to Antonio Rasura, Director, Motion Picture Services at the Eastman Kodak Company who gave me a lot of help on the use of cine film in sound ranging equipment.

In a story straight out of Mickey's 'Do Not Do This' file, having captured Grandcourt, 57 Brigade wander off, caught up in that strange lapse of concentration that affects combat units once they have taken their objective. But part of it is held and the British line will not be so dominated that winter.

A quick thank you to Antonio Rasura, Director, Motion Picture Services at the Eastman Kodak Company who gave me a lot of help on the use of cine film in sound ranging equipment.

I'm sorry but I don't know who has the copyright for this amazing picture. I hope they will excuse me using it to show what sound-ranging looks like (as well as being an amazing picture in its own right).

Related Episodes

Related Episodes