Celestine - addicted to War?

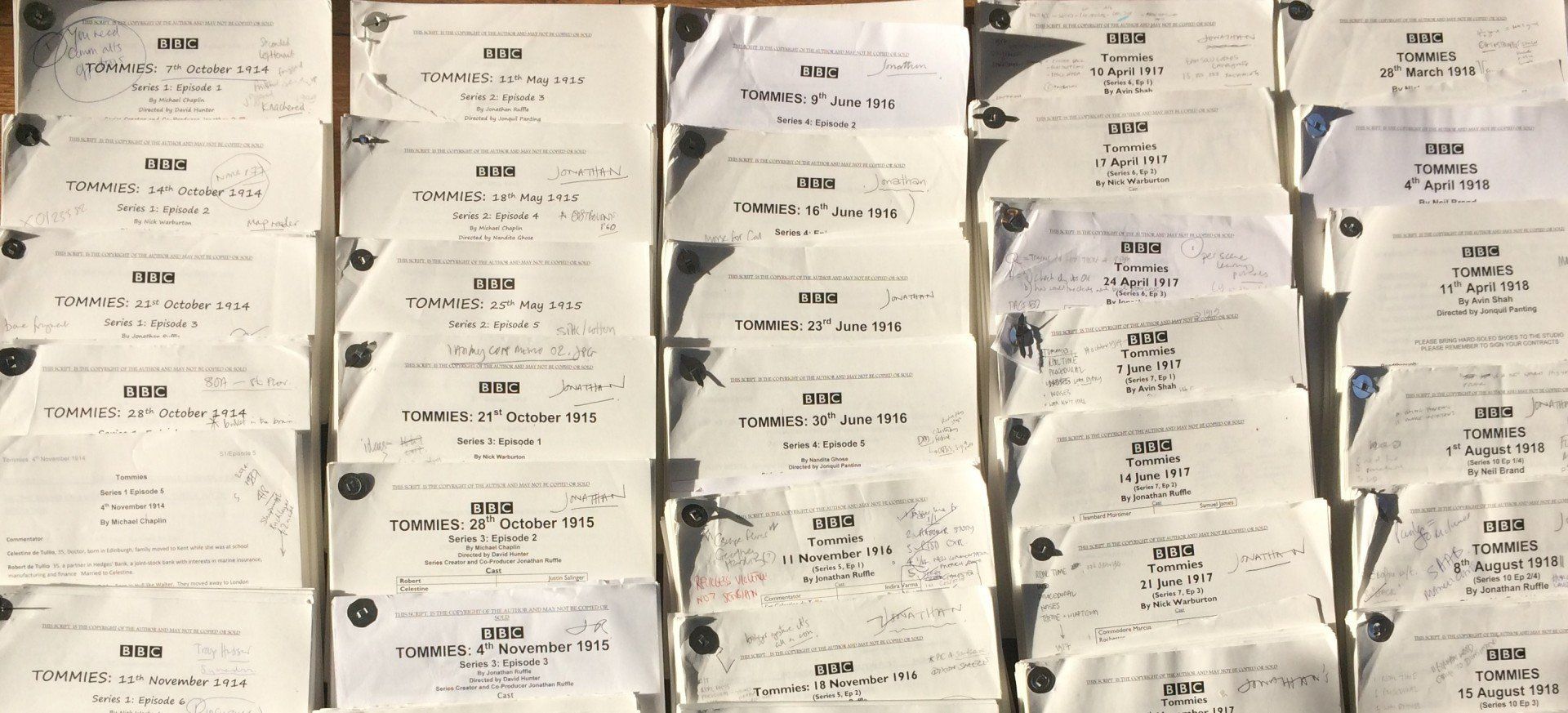

11th November 1916

This is an episode set in the fighting to take the town of Bitola, the key to the Macedonian mountains.

So much of the story was adapted from Flora Sandes' memoir which you can read at the IWM Library or buy for a tidy sum at a second hand bookshop – it is called THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A WOMAN SOLDIER. Flora was the only British woman to take part in combat in WW1, and at this time she was fighting as a Sergeant Major in the 4th Company, 1st Battalion, 2nd Infantry regiment, of the Mareva Division of the Serbian Army.

Most of the combat incident in this episode occured on the 15th November 1916 on Hill 1212 when Flora was nearly killed.

You can read more about Flora in THE LOVELY SERGEANT by Alan Burgess and A FINE BROTHER, a recent and excellent book by Louise Miller.

I based the character of Olive on Olive King, an Australian nurse who left the Scottish Women's Hospital in Ostrovo to become a driver for the Serbian Army. More about that in ONE WOMAN AT WAR by Hazel King. And the character of Gordana is based on Milunka Savic who was a sergeant in the Serbian Army you can read more about

here. At the bottom of the page you've got Olive and Flora as well.

I made one very early decision that offended my historical sense but seemed important. The soldiers would have called grenades -bombs. As in Mills bombs. But I just found everyone saying 'bomb' in the script, even with a line from the Commentator explaining what was meant near the top of the episode, didn't really work. In those moments of crisis, and there were plenty involving grenades in this episode, clarity had to come first. Apologies.

This was winter mountain warfare, and the reason for the push on Bitola is explained here – I know I say Monastir but I filmed this on a research trip eighteen months ago and I didn't know at the time that the Serbs would have called the town Bitola.

Some context: the Serbs were hounded from their homeland by an invading army of the Central Powers in 1915, and almost unbelievably retreated through neighbouring Albania to spend the winter on the Greek island of Corfu. Their return and fight back is legendary: 60% of the male population was killed in WW1.

The Serbs were fighting in what might broadly be called the middle of the line, with the French to the left and the British on the right. The slowness of progress meant that the British troops dug in round their port and base, Salonika (now Thessaloniki) they were nicknamed 'The Gardeners' because of their inactivity. More about them in their own episode in 1917.

Soldiers are overly interested in providing bathing and toilet facilities for females, a sort of twisted acknowledgement of body differences while apparently brusquely acting as providers. This happened to WW1 nurses on the Western and Russian fronts.

The latter half of this episode explored Celestine's new psychological awakening. It's been a year since she told Mickey that she was addicted to war, but self-knowledge counts for zip when you are in the midst of addiction. Some people are addicts all their lives without taking action, so in some respects a year is a blink of an eye. But this one has been made all the worse because Celestine knows she has to change.

She's met Serbian soldiers - exhibiting a particular kind of mental, physical and spiritual calm in the sea of violence - who are rejecting war's glamour and desensitisation. They are practising a new way of life. As a doctor she might be aware of the early medical breakthroughs of the Christian groups trying to cure alcoholism: acceptance of the problem leading to a talking cure anchored in some self-defined spiritual belief.

She's effectively having her first 'War Addicts Anonymous' meeting (truly a moment of staggering Grace in the lives of real-life addicts) in the middle of a war.

I was led in my writing of this latter half of the play by addicts who generously shared intensely personal insights with me, one in particular being ex-military who had suffered acute PTSD. I thank them all, and they remain as we agreed, completely anonymous.