War in East Africa

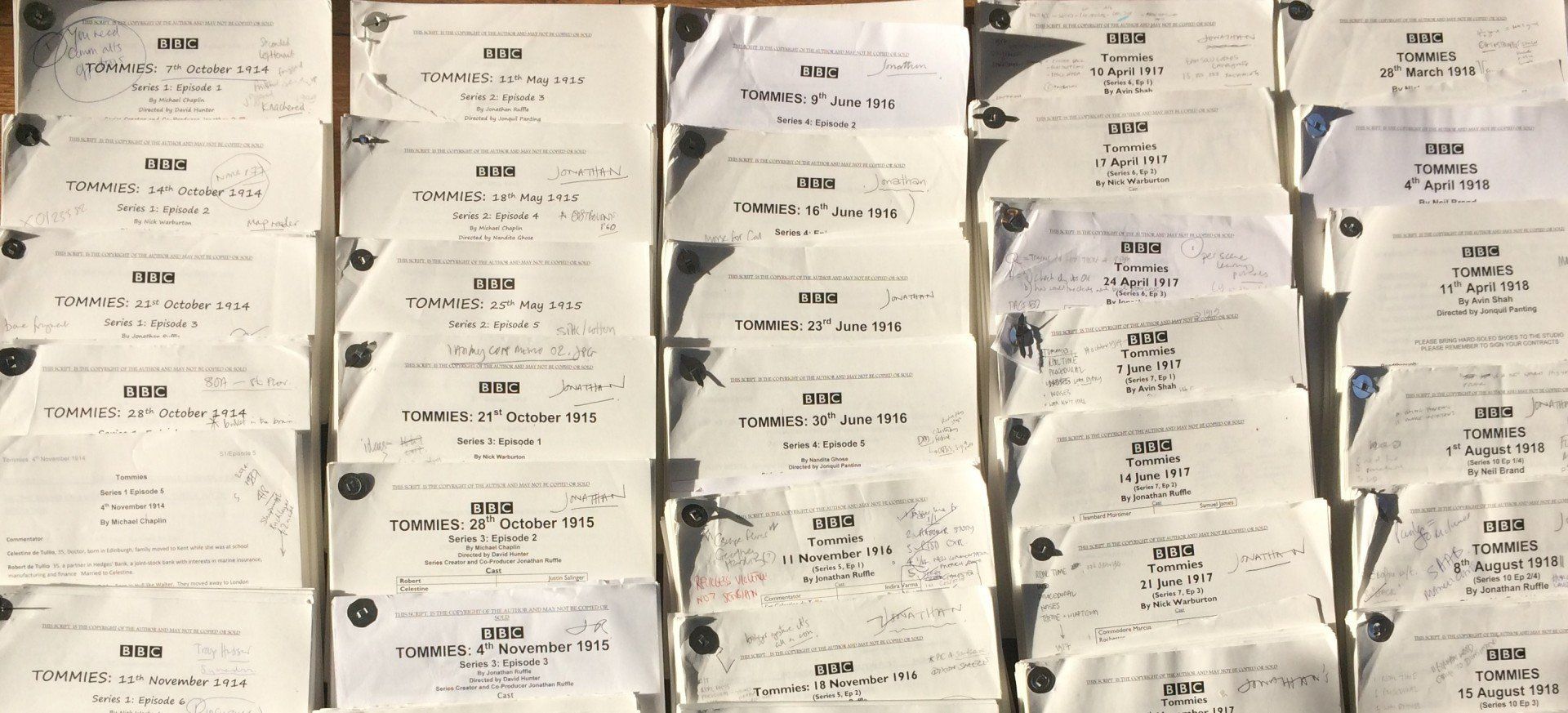

7th June 1917

7th June 1917

TOMMIES is about the signals war, and I knew we wanted to go to East Africa as soon as possible. This extraordinary campaign was the longest of any on land in the First World War. Indeed, the first shot by a British Empire serviceman in WW1 was fired by an African soldier in the West African Frontier Force well before anything on the Western Front. And the Germans were never defeated in Africa - their leader signing a surrender document a full two weeks after peace in Europe. Indeed, he returned in triumph to Berlin to pass through the Brandenburg gate in March 1919.

Signals? Well. They had to string telephone cables above 25 feet or they'd be destroyed by giraffes.

Today's drama, written by Avin Shah, was one of the most challenging to research. Only Nalder's HISTORY OF THE ROYAL CORPS OF SIGNALS and the Indian HISTORY OF THE CORPS OF SIGNALS gave any signals background and there wasn't even an Official History of the Campaign. Or so I thought - I found a draft version in the National Archives.

All the events at Mkalama were as usual, accurate to the minute, though we had to speculate on how events played out in the fort. This was a jigsaw puzzle from the war diaries (mainly those of the Nigerian Brigade in the NA) and some scanty use of the main published sources on the period, TIP AND RUN by Edward Paige (very good) and the rather odd THE BATTLE OF THE BUNDU by Charles Miller. I say odd because he declares in his intro that when he's heard a story that seems better than the facts he'll go with the story, which makes him redundant as a serious source.

Hew Strachan's THE FIRST WORLD WAR IN AFRICA and David Olusoga's THE WORLD's WAR were great early reads to get an overall view, crucial in this campaign because at any one moment the Germans are fighting with different columns in different parts of the continent, and everything is mobile.

I got a lot of colour from Hawtrey's, Deputy Director of Signal's war diary at GHQ. He gave us the mixed compostion of Z Force Signals, although that had also been in the Indian History as above. A lot of his paperwork was on the backs of old recycled German signals forms, and this bloke is a proper senior officer.

Hew Strachan's THE FIRST WORLD WAR IN AFRICA and David Olusoga's THE WORLD's WAR were great early reads to get an overall view, crucial in this campaign because at any one moment the Germans are fighting with different columns in different parts of the continent, and everything is mobile.

I got a lot of colour from Hawtrey's, Deputy Director of Signal's war diary at GHQ. He gave us the mixed compostion of Z Force Signals, although that had also been in the Indian History as above. A lot of his paperwork was on the backs of old recycled German signals forms, and this bloke is a proper senior officer.

Also in this diary was the dialogue and originals about using cipher (code) to send messages, which is dodgy because cipher messages go first, and all other private messages have to be paid for. There is even one message that breaks the golden rule of code, and I mean that, in that it mixes code and plain language. You can easily guess from the rest of the message that they want whisky, so armed with knowing those letters JUTBAQ means WHISKY you are a quarter of the way to solving what must be a very simple code. (And before you say, how come he can use these pictures of TNA original documents when he won't show us any of the others, while moaning on about copyright - well, I was told I could use this one and the one in the heading by a bloke who works there. I've just used them here as well as in the place he actual gave permission for them, is all.)

Melvin Page's MALAWIANS IN THE GREAT WAR AND AFTER, 1914-1925 is nothing short of brilliant. He's got hold of interviews from serving askaris and tengatenga men, exactly the stories we'd expect to have been lost to history. This is the EA war from the African perspective, nailed. Women's perspective, economic costs, it is all in here. The quotes read like they were copied down by someone in a centralised manner, but not bad for all that.

Melvin Page's MALAWIANS IN THE GREAT WAR AND AFTER, 1914-1925 is nothing short of brilliant. He's got hold of interviews from serving askaris and tengatenga men, exactly the stories we'd expect to have been lost to history. This is the EA war from the African perspective, nailed. Women's perspective, economic costs, it is all in here. The quotes read like they were copied down by someone in a centralised manner, but not bad for all that.

The brilliant KAISERS HOLOCAUST by Olusoga and Erichsen is a disturbing book on how Germans in German West Africa were running concentration camps, genocide, and twisted medicine 30 years earlier than the Holocaust. KING LEOPOLD's GHOST by Adam Hochshild was similar grittily awful about the Belgian Congo.

WITH THE NIGERIANS IN G.E.A. by Downes was wonderfully detailed stuff up and including 070617 when they hear the Germans are besieging Mkalama, detail of their attack; details of shells buried in walls, and the stuff about the "traitor" askaris. It then rather frustrating tails off as Downes himself I suppose didn't go towards the attack itself, instead staying with the column.

WITH THE NIGERIANS IN G.E.A. by Downes was wonderfully detailed stuff up and including 070617 when they hear the Germans are besieging Mkalama, detail of their attack; details of shells buried in walls, and the stuff about the "traitor" askaris. It then rather frustrating tails off as Downes himself I suppose didn't go towards the attack itself, instead staying with the column.

Before I go on to a summary of the action we revisited for the episode, some general thoughts about the campaign.

This is an African drama. The First World War in Africa was, to quote a Tanzanian historian, "the climax of Africa's exploitation: its use as a mere battlefield". The East African campaign is almost completely off the British WW1 cultural map.

The war directly or indirectly affected 50m people: in British East Africa 83% of local manpower was drafted. Second only as a body-blow to growth to the slave trade to the Middle East and India, this war between the Europeans devastated an area five times that of Germany, and killed 10% of the 2m Africans who served. Involving troops from races and countries from all over Africa, it was a sort of civil war: but with no chance of liberation at the end of it. In fact, increased oppression was on the cards.

This is an African drama. The First World War in Africa was, to quote a Tanzanian historian, "the climax of Africa's exploitation: its use as a mere battlefield". The East African campaign is almost completely off the British WW1 cultural map.

The war directly or indirectly affected 50m people: in British East Africa 83% of local manpower was drafted. Second only as a body-blow to growth to the slave trade to the Middle East and India, this war between the Europeans devastated an area five times that of Germany, and killed 10% of the 2m Africans who served. Involving troops from races and countries from all over Africa, it was a sort of civil war: but with no chance of liberation at the end of it. In fact, increased oppression was on the cards.

Why was there fighting in Africa in WW1?

Simple: the Germans wanted to prick at the extremities of Britain's empire and force her to divert troops and resources from the Western Front.

The answers to why we know so little about it are legion.

The first is that the British lost. They chased a determined German guerrilla-style leader and his native troops around for five years and never caught him: he surrendered two weeks after the armistice in 1918.

The second is the massive waste of lives for such a nil return. There were some European troops but the fighting and portering was done by native Africans. In British East Africa alone the death toll among local recruits was 45,000, a crippling one-in-eight of the male population.

The third is that most of these men were victims of illness: distinctly unglamorous, with echoes of Imperial jaunts of the previous century. At least the Western Front was now killing more men by violence than disease. Here in Africa 2 out of 3 succumbed to illness. It was the same story for Africans and Europeans, with disease taking those supposed to be the hardier only slightly less than the incomers.

Simple: the Germans wanted to prick at the extremities of Britain's empire and force her to divert troops and resources from the Western Front.

The answers to why we know so little about it are legion.

The first is that the British lost. They chased a determined German guerrilla-style leader and his native troops around for five years and never caught him: he surrendered two weeks after the armistice in 1918.

The second is the massive waste of lives for such a nil return. There were some European troops but the fighting and portering was done by native Africans. In British East Africa alone the death toll among local recruits was 45,000, a crippling one-in-eight of the male population.

The third is that most of these men were victims of illness: distinctly unglamorous, with echoes of Imperial jaunts of the previous century. At least the Western Front was now killing more men by violence than disease. Here in Africa 2 out of 3 succumbed to illness. It was the same story for Africans and Europeans, with disease taking those supposed to be the hardier only slightly less than the incomers.

Fourthly, it cost so much money. The East Africa campaign cost £70m in 1918 prices, or £6.4bn equivalent in 2017 prices. The total expenditure for all the Empire forces involved in Africa was around £250m or £23bn equivalent.

Fifthly, set piece battles were few, which gives the campaign few hooks for the uninitiated to hang on to. You could trek for days and just miss the party you were hunting. The density of the foliage was such whole armies could pass within yards and be mutually unaware of each other. Mkalama - where our action is set - was 360 miles from HQ in Dar es Salaam: that is London to Edinburgh, all across unconventional terrain.

The sixth was the rape of the land, alluded to above. The Europeans commanded armies, patrols and columns that lived off the land, conscripted forcibly, and put a brake on the development of East Africa that lasted decades. That was a story best hushed-up, or even better, blamed on the continuing fecklessness and technological naivety of the locals.

Fifthly, set piece battles were few, which gives the campaign few hooks for the uninitiated to hang on to. You could trek for days and just miss the party you were hunting. The density of the foliage was such whole armies could pass within yards and be mutually unaware of each other. Mkalama - where our action is set - was 360 miles from HQ in Dar es Salaam: that is London to Edinburgh, all across unconventional terrain.

The sixth was the rape of the land, alluded to above. The Europeans commanded armies, patrols and columns that lived off the land, conscripted forcibly, and put a brake on the development of East Africa that lasted decades. That was a story best hushed-up, or even better, blamed on the continuing fecklessness and technological naivety of the locals.

The seventh was that the war had put imperialism itself, and all its high-minded talk of a civilising mission, on trial. Germany had a genocidal history behind its colonies, now it unleashed those forces in a classic raid-and-burn guerrilla war.

The eighth is the last, but possibly no less important for that. Had there been no Western Front the war in Africa would have boggled the mind for with its sheer scale and audacity and dominated the front pages of the world. It was a tragedy, however, that took the stage when other tragedies were there to overshadow it.

Thus the other aspects of the campaign often alluded to in the admittedly rather patronising writing (echoing the US experience in Vietnam) about the grace of the people, the beauty of the country, the mind-bending variety of wildlife – elephants, lions and crocodiles get regular mentions, but attacks by bee swarms are the most easily triggered and therefore most common - and the sheer extraordinariness of the experience (imagine you came from the urban squalor of Manchester, Dusseldorf or Calcutta), have all been shoved to the back of the cupboard along with everything else.

The eighth is the last, but possibly no less important for that. Had there been no Western Front the war in Africa would have boggled the mind for with its sheer scale and audacity and dominated the front pages of the world. It was a tragedy, however, that took the stage when other tragedies were there to overshadow it.

Thus the other aspects of the campaign often alluded to in the admittedly rather patronising writing (echoing the US experience in Vietnam) about the grace of the people, the beauty of the country, the mind-bending variety of wildlife – elephants, lions and crocodiles get regular mentions, but attacks by bee swarms are the most easily triggered and therefore most common - and the sheer extraordinariness of the experience (imagine you came from the urban squalor of Manchester, Dusseldorf or Calcutta), have all been shoved to the back of the cupboard along with everything else.

But guess whose story encapsulates warfighting in Africa? Signallers: because in East Africa they potentially held the key to the whole problem of knowing where your highly mobile enemy was headed, and move to intercept him. Wireless was the answer. Telephone line came a poor second, endlessly cut or pinched by the enemy, falling from posts that rotted in days, and vulnerable to giraffes if slung below 25 feet.

I had to pick a story to tell. And June 1917 in East Africa is a golden opportunity for stories, as well as a honeyed trap.

We know the basic idea: Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck led a guerrilla army of German troops and native levies (called askaris) around Africa while being fruitlessly pursued by British, Indian, South African, Belgian and African contingents. These latter came from all over, not just the locals – expect Nigerians from 2000 miles away (that's London to Cairo). Von L-V romped in and out of German, Portuguese and British East Africa as well as the Belgian Congo (other campaigns were fought in West and South West Africa by other German leaders).

A further problem is that Von L-V didn't lead one army, he divided his forces into at least four different columns, sometimes separated by hundreds of miles. The British had to divide their resources accordingly.

I had to pick a story to tell. And June 1917 in East Africa is a golden opportunity for stories, as well as a honeyed trap.

We know the basic idea: Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck led a guerrilla army of German troops and native levies (called askaris) around Africa while being fruitlessly pursued by British, Indian, South African, Belgian and African contingents. These latter came from all over, not just the locals – expect Nigerians from 2000 miles away (that's London to Cairo). Von L-V romped in and out of German, Portuguese and British East Africa as well as the Belgian Congo (other campaigns were fought in West and South West Africa by other German leaders).

A further problem is that Von L-V didn't lead one army, he divided his forces into at least four different columns, sometimes separated by hundreds of miles. The British had to divide their resources accordingly.

The trap, then, is the many simultaneous incidents across a vast area, a veritable dust storm of place names and names of column leaders. Instead of colour and interest, confusion rapidly sets in. There were at least three actions around this time I had to research, but I plonked for only the most vivid. Remembering that at any given moment there are thousands of men trekking around Africa, we are with just one unit finally catching up with just one of von L-V's sub-units, one in the middle of what we would now call Tanzania, led by a German officer called Naumann.

On today, 7th June 1917, in history, Naumann is moving through the bush causing as much damage as he can. You should think of his force as being about 170 askaris (trained native troops, mainly Bagandan and Nubians), probably 300 local porters, and only 15 Europeans. He has three machine guns and some very light field artillery. Naumann knows that his general direction of movement will be reported to the British as threatening distant Nairobi, capital of British East Africa, and make everyone sh#t themselves.

He's besieging a British fort at Mkalama (4°6'56.89"S, 34°38'38.45"E on Google Earth) a place freighted with all the paradoxes and contrariness of the African campaign.

It was originally a German fort – we're in what was German East Africa at this location. The fort itself is currently held by only about twenty native troops and two British local government officials. They have to communicate in German, as the troops are all ex-German askaris who have run away from one bunch of colonials only to be press-ganged by this new lot.

On today, 7th June 1917, in history, Naumann is moving through the bush causing as much damage as he can. You should think of his force as being about 170 askaris (trained native troops, mainly Bagandan and Nubians), probably 300 local porters, and only 15 Europeans. He has three machine guns and some very light field artillery. Naumann knows that his general direction of movement will be reported to the British as threatening distant Nairobi, capital of British East Africa, and make everyone sh#t themselves.

He's besieging a British fort at Mkalama (4°6'56.89"S, 34°38'38.45"E on Google Earth) a place freighted with all the paradoxes and contrariness of the African campaign.

It was originally a German fort – we're in what was German East Africa at this location. The fort itself is currently held by only about twenty native troops and two British local government officials. They have to communicate in German, as the troops are all ex-German askaris who have run away from one bunch of colonials only to be press-ganged by this new lot.

When Naumann arrived four days ago he called on the British to surrender and was refused, at which point Naumann threatened to execute as traitors all the ex-askaris upon the fall of the fort, which led to perilous unrest within. Naumann then shelled the fort not only to reduce it, but in the hope he'd hit one of the numerous mines and charges inserted but not blown in the walls, put there by the Germans when they left the fort six months earlier (unbeknown to Naumann these had been removed by the British). So today 7th June 1917 the fort is hours away from falling as the ex-askaris are planning to buy their lives by handing the Brits over to the Germans.

So there's an interesting powder keg in the fort (in two senses) and outside it indicative of the campaign overall. Hoofing towards Mkalama are several different columns with names various of their commanders. But we are concentrating on the one that gets there first, a column led by Lieutenant Colonel Sargent including Nigerian and Belgian troops. Think of this force as about 100 Nigerians of 4/Nigerian regiment, 100 Belgians of XIII/Belgian regiment, and 10 Europeans. The Nigerians are Nigerians, and the 'Belgians' are Congolese natives. And about 500 porters, local to East Africa.

We know from the Indian Signallers' History that a Z Signals unit was sent with this force, although gratifyingly they make no appearance in any of the unit histories except by implication, so we can place them where they are most effective in story-telling terms.

So there's an interesting powder keg in the fort (in two senses) and outside it indicative of the campaign overall. Hoofing towards Mkalama are several different columns with names various of their commanders. But we are concentrating on the one that gets there first, a column led by Lieutenant Colonel Sargent including Nigerian and Belgian troops. Think of this force as about 100 Nigerians of 4/Nigerian regiment, 100 Belgians of XIII/Belgian regiment, and 10 Europeans. The Nigerians are Nigerians, and the 'Belgians' are Congolese natives. And about 500 porters, local to East Africa.

We know from the Indian Signallers' History that a Z Signals unit was sent with this force, although gratifyingly they make no appearance in any of the unit histories except by implication, so we can place them where they are most effective in story-telling terms.

A quick bit of background. From 1914 it was obvious how important signallers would be in East Africa, and soon even more obvious that disease and dispersion of these valuable men would spread them ridiculously widely. During 1915 the British gave up on the usual battalion signaller and Royal Engineer Signals Service partnership we see on the Western Front, and embarked on a policy of placing any signaller arriving off the boat in just the one unit, the dramatically named "Z Signals Service". It didn't matter what skill-base, nationality or rank you had. If you were a signaller, you were next out the door heading wherever you were needed.

We know from our previous WF experience that units with no shared esprit de corps find it hard to bond in battle. This however was not true of the disparate men of Z Signals. The glue for them was the physical and mental challenge of signalling itself. However, this in no way means that on all other matters they are as distrustful, mocking and prone to petty violence as any group of Geordies (as we saw on the Somme), for example. Z Signals which had done so well for two years was to be split up again in the next few weeks to better suit the new formal arrangements for columns, but I think they'd be bonded all the more for their remaining days together.

So these signallers are with Sargent's Column, approaching Mkalama fort on the morning of the 7th June 1917 along rocky paths and through tough spiny vegetation. Water and food are short. It's blindingly hot. It's another day's heartbreakingly pointless trudge in prospect, more than likely they'll get lost and fail to relieve the fort before coming upon it as the long passed scene of a massacre. Suddenly the Nigerians and Belgians collide with Naumann's rearguard whom he has posted ten miles down the road to watch for just such an eventuality.

We know from our previous WF experience that units with no shared esprit de corps find it hard to bond in battle. This however was not true of the disparate men of Z Signals. The glue for them was the physical and mental challenge of signalling itself. However, this in no way means that on all other matters they are as distrustful, mocking and prone to petty violence as any group of Geordies (as we saw on the Somme), for example. Z Signals which had done so well for two years was to be split up again in the next few weeks to better suit the new formal arrangements for columns, but I think they'd be bonded all the more for their remaining days together.

So these signallers are with Sargent's Column, approaching Mkalama fort on the morning of the 7th June 1917 along rocky paths and through tough spiny vegetation. Water and food are short. It's blindingly hot. It's another day's heartbreakingly pointless trudge in prospect, more than likely they'll get lost and fail to relieve the fort before coming upon it as the long passed scene of a massacre. Suddenly the Nigerians and Belgians collide with Naumann's rearguard whom he has posted ten miles down the road to watch for just such an eventuality.

Fighting starts at 0800. The rearguard, probably only 50 blokes, are outnumbered but they skilfully withdraw in the direction of Mkalama to hook up with the rest of Naumann's force. This takes until 1500 when they are three and a half miles south of the fort. Here the path narrows, and against their now augmented enemy, the Nigerians and the Belgians really have to push to get up the fort by 1630.

Fearing a flanking trap, Sargent's column swings north and digs in two-thirds of a mile north of the fort. Both sides stop firing (bullets being at a premium) at 1800. It was also getting dark.

The Allies were joined at 0230 the following morning by the rest of Sargent's column and after sending scouts in at 0800, went into Mkalama that lunchtime to find that Naumann had pulled out overnight. He was far away by now.

Mkalama was thus relieved, just before the revolt by the askaris came to fruition and the murder of their own officers carried out.

Fearing a flanking trap, Sargent's column swings north and digs in two-thirds of a mile north of the fort. Both sides stop firing (bullets being at a premium) at 1800. It was also getting dark.

The Allies were joined at 0230 the following morning by the rest of Sargent's column and after sending scouts in at 0800, went into Mkalama that lunchtime to find that Naumann had pulled out overnight. He was far away by now.

Mkalama was thus relieved, just before the revolt by the askaris came to fruition and the murder of their own officers carried out.

Related Episodes

Related Episodes