Arras. Bloody Arras.

10th April 1917

10th April 1917

10th April 1917

Unusually I set our drama on the day after the famous and highly successful attack at Vimy and Arras, the 9th April 1917. This was so we could challenge the myths around that success in context - otherwise we'd have be trying to make that analysis during a flurry of rolling successful actions, which would have just put Mickey in a corner moaning away as everything was going well.

Vimy Ridge was the name given to the northern end of a bigger front attacked on Easter Monday 1917 at Arras. The whole attack was made by the British Army supporting the 'real' attack going in further south by the French Army. That old favourite.

Vimy Ridge was the name given to the northern end of a bigger front attacked on Easter Monday 1917 at Arras. The whole attack was made by the British Army supporting the 'real' attack going in further south by the French Army. That old favourite.

(Pictures on this page a bit bigger than normal as they're mostly underground in the Vimy Tunnels.)

The British put a huge and controlled effort into this operation before, during and after.

Huge: finally the right amount of artillery, physical preparation, planning, Intel and training went into the attack.

Huge: finally the right amount of artillery, physical preparation, planning, Intel and training went into the attack.

Controlled: more difficult to explain. Try this - for the Somme, they shelled the enemy's defences, and then went over the top. Contrast that with Vimy/Arras – they shelled specific targets behind the German's defences and didn't waste shells on bare earth; they shelled to neutralise targets and then moved on, not continued to pointlessly hammer away to destroy them; they left German observation posts and telephone exchanges alone until smashing them just before the attack to paralyse comms at a key moment; they used the new Fuse 106 on their shells which actually cut barbed wire (hurrah); they perfected the rolling barrages that helped the infantry during the attack; and then artillery became available to the infantry as they were consolidating the ground gained, to protect them from counter attack.

Before, during and after: never before had a British attack been scaled to provide a coherent service to the men in the line. Previously everyone did their bit as hard as they could. Now they were acting together.

Pausing only to say this is exactly in line with Mickey's thinking, the attack involved no less than three British Armies, the First, Third and Fifth, and incorporated within them Australian, Canadian, New Zealand and South African troops.

Let us consider the northern end of the attack, which as I said above was effectively the lump of Vimy Ridge.

Before, during and after: never before had a British attack been scaled to provide a coherent service to the men in the line. Previously everyone did their bit as hard as they could. Now they were acting together.

Pausing only to say this is exactly in line with Mickey's thinking, the attack involved no less than three British Armies, the First, Third and Fifth, and incorporated within them Australian, Canadian, New Zealand and South African troops.

Let us consider the northern end of the attack, which as I said above was effectively the lump of Vimy Ridge.

This objective was given to First Army, which included 1 Corps, 17 Corps and the Canadian Corps. The Canadians were tasked with the main body of the 'lump', with 1 and 17 Corps at the top and bottom. For this reason, Vimy Ridge is seen by the Canadians as 'theirs' and the attack as an important step in nationhood (the Canadian Memorial at Vimy is second only in size to the one at Thiepval). There are a number of problems with this, which I'll detail below. But I should say I hold no animus against Canadians, I just think this is an overlay by subsequent political minds and would be unrecognisable to the men on the ground.

Canada had Dominion status from the 1870's and faced intriguing problems of identity, not least the large French-speaking population and the immigrant communities from Germany which challenged Canadian unity in the war years. But the motive of Canadians on the ground at Vimy was to stand shoulder to shoulder with Englishmen, and it should not be forgotten that a lot of them were English who had gone out as settlers and had come back to fight. Their commander, Byng, was English, as was his staff. (Perhaps the need for a Canadian identity can be expressed best by Prime Minister Mackenzie King who quipped that Canada was a country with "not enough history, too much geography".)

The notion of an independent attack also holds no military water. Had the four Canadian divisions attacked Vimy Ridge on their own, it would have been a disaster. We've done enough tactical stuff on TOMMIES now for us to know that taking a German fortress requires a wide weight of attacking forces, not just on the pressure point. Support is all.

And furthermore, even the notion of the Canadian divisions attacking on bloc doesn't work either. Their artillery support was from the British 5th Division, and when the final plan was submitted to First Army, it was obvious that one area would fail as it was too difficult for the number of Canadians available. Therefore a British Brigade - 13th Brigade - was put forward to attack with them. No one in the Canadian ranks said - 'no thanks, we'd prefer to go in and be killed rather than have your help'.

But the biggest point of the lot is the one we had earlier. The entire Vimy/Arras plan was a coherent one of mutual planning and support. The myth of the Canadians dashing up Vimy Ridge brandishing some sort of unique Canuck pluck serves no-one. Mickey would have hated that idea because the notion that anyone might slide back to believing such a 1914-and-earlier idea is highly disturbing. And lethal.

Mickey's with his own blokes on 10th April 1917, 1st Battalion Royal West Kents and 2nd Battalion King's Own Scottish Borderers, in the 13th Brit Brigade, and he's liaising with the men of the 29th (Vancouver) Infantry battalion of the 6th Canadian Bde on the left and the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles of the 8th Canadian Brigade on the left.

If you ever go to Vimy you'll see the extraordinary subways built by the Canadians to get their men to the front. These tunnels, as big as a building corridor, stretch from up to a mile behind the front line up to and sometimes beyond into No Man's Land. There were twelve in total (they have one you can visit) and they provided both secrecy and safety. The Germans didn't know that men were effectively queuing to attack them and they were too deep in the chalk to get them even if they'd known. Remember also how every previous attack we've ever done has had men shelled while preparing to go over? Not here, by definition.

The British shelling had been precise, lacking in waste, and discontinuous. This artillery pattern meant the Germans didn't know when they were coming, and the sheer number of troops emerging from their tunnels was totally unexpected and physically and emotionally overwhelming.

In one respect, however, the Germans did know we were on our way: they were in fact even better informed than during the Somme build-up about Allied intentions. There were three massive French leaks, one of which was the Germans capturing a French NCO with the plans in his pocket five days ago. As a result, the Germans increased their gun batteries in this area from 53 to 392 by 15th April, the time of the French attack.

The British shelling had been precise, lacking in waste, and discontinuous. This artillery pattern meant the Germans didn't know when they were coming, and the sheer number of troops emerging from their tunnels was totally unexpected and physically and emotionally overwhelming.

In one respect, however, the Germans did know we were on our way: they were in fact even better informed than during the Somme build-up about Allied intentions. There were three massive French leaks, one of which was the Germans capturing a French NCO with the plans in his pocket five days ago. As a result, the Germans increased their gun batteries in this area from 53 to 392 by 15th April, the time of the French attack.

There's an irony here. By bringing their batteries within range they offered them up to the scrutiny of the sound rangers, flash spotters, other ground observers, and No. 16 Squadron attached to the Corps. Therefore eighty-three percent of the estimated 212 German batteries threatening the Canadian Corps were located and targeted - effectively mastering the German guns. Indeed, at one point along 2nd Division's front, there was no German artillery response for seven minutes as the troops crossed No Man's Land, which is quite extraordinary.

The British also used a new shell fuse, the 106, which exploded instantly on contact and therefore destroyed barbed wire. The Allies had four lines of defence to take, and certainly in this sector they got them all using an incredibly detailed creeping barrage with well executed pauses and units leap-frogging one another to keep the freshest troops to the fore.

The weight of shells was extraordinary. By the spring of 1917 the British Army had grown to encompass sixty-two divisions and a strength of more than one and a half million men. The scale of the battle is portrayed by the number of divisions that participated – twenty-six infantry and three cavalry divisions. The intensity of the battle can accurately be inferred, for example, from the availability to the British Army of heavy guns, howitzers and ammunition. Comparing second quarter figures, the number of heavy guns and howitzers increased from 761 in 1916 to over 1,500 pieces in 1917. The number of rounds of heavy ammunition the British Army received during the same quarterly periods had increased from more than 700,000 rounds to more than 5,000,000 rounds. So that is twice the number of guns and nearly ten times the number of shells on the Somme.

It doesn't take a Robert de Tullio to work out that in sheer financial terms this bombardment cost £17m at 1917 prices or over £1bn at today's. There's a question whether they can actually afford to do many more attacks like this, however successful, notwithstanding the wear and tear on the barrels of the guns.

A big plus however, on lots of levels, was that the Allies had broken into the vaunted Hindenburg Line rather than the old line at say the Somme. Imagine you were the Germans. You've poured six months of labour and ingenuity into a new system of clever interlinked firebases and staffed them with flexibly trained troops given the latitude to hold or pull back or even advance on their own initiative. There were deep killing zones over which attacker would have to plod while preregistered artillery could smash them to bits.

Depth, however, is very expensive. It had cost a fortune in money and man-hours. True, Vimy Ridge was so narrow the deep new system couldn't really function here, (Byng had harassed them with artillery to make sure they couldn't readily change anything), but that wasn't the case further south and must have been very demoralising.

There had been a change in British infantry tactics. The infantry had been instructed, if their attacking neighbours were held up by anything, that they should immediately turn and help attack the Germans causing the problem. Meanwhile, they could be confident that elsewhere in the line reinforcements were pushing through where things were more successful. This ended all those dread years of putting fresh troops into losing situations.

Following on from this, the tactic for the whole operation was 'Bite and Hold'. The principle was not to advance further than your guns could protect the men. Consolidation of captured ground was so important men were ordered not to advance unless men could be spared.

Tanks had been deployed, all had broken down. But in a masterpiece of co-ordination, their arrival at the front line the day before had been masked by selective use of artillery to smother the noise. Imagine that.

In the build-up the Canadians had kept their intelligence officers and men in the same area so they could gain an intimate knowledge of the area opposite them via observing, data crunching and raiding. They called the department the Scouts, and it had high status so everyone wanted to contribute. Compare this to the British Army for whom "military intelligence? That's a contradiction in terms" is seen as a world-class witticism. The Scouts maintained a Log Book so everything could be entered into it, updated and passed onto the next shift. (Mickey would be in his element.) Because it was local intel for a local attack, remarkable things could be achieved: German tunnels deliberately left unshelled so they could be used in the future.

Something else Mickey would have liked was a catholic approach to varied signals kit. The Canadians were keen on using new valve wireless sets operating on continuous wave technology, not those rackety spark-gap transmitters we've been using up to now. Valves also made everything smaller and lighter. Aeroplanes (remember the panneau and klaxon system?) were used a lot.

The Germans had completely penetrated the main British frontline cipher in April 1917. But at Vimy Ridge, for the first time in a year, an Imperial corps exceeded the Germans in the quality of signals intelligence. Using twice the normal complement of listening sets, the Canadian Corps acquired some of the extremely detailed information required for this operation and prevented the normal Canadian garrulousness from forewarning the Germans. Signals security was doubly crucial here. Since the Germans had become accustomed to detecting major British operations through their listening sets, the mere absence of such indications may have put them off guard.

Something else Mickey would have liked was a catholic approach to varied signals kit. The Canadians were keen on using new valve wireless sets operating on continuous wave technology, not those rackety spark-gap transmitters we've been using up to now. Valves also made everything smaller and lighter. Aeroplanes (remember the panneau and klaxon system?) were used a lot.

The Germans had completely penetrated the main British frontline cipher in April 1917. But at Vimy Ridge, for the first time in a year, an Imperial corps exceeded the Germans in the quality of signals intelligence. Using twice the normal complement of listening sets, the Canadian Corps acquired some of the extremely detailed information required for this operation and prevented the normal Canadian garrulousness from forewarning the Germans. Signals security was doubly crucial here. Since the Germans had become accustomed to detecting major British operations through their listening sets, the mere absence of such indications may have put them off guard.

We know Mickey isn't a man for doing things by the book but he uses the two new handbooks of collected wisdom to run this battle. Gone are the days when all arms of the army ordered far too many lines far too late. And if signals weren't about laid their own anyway - artillery, I'm talking to you. The book - the SS148 - was the result of a an eight-day writing panic after a conference in February 1917, but now it is saving misdirected effort and therefore energy and lives. Lines could not be laid unless they were sanctioned by the Signals Service. And while we're here, the new signals rulebook also said that lines should be laid forward as stingily as possible, an end to the ridiculous demands made on signallers over many months. Now just a metallic pair for the Brigade Commander and a pair for the artillery, furthermore routed through places as they go forward that the Brigade Commander would find himself in an attack. This is a huge change from lines being laid and then the Brigade Commander sets up shop elsewhere. Simple, but so ground-breaking.

But the thing Mickey would have liked I think the most of all was the psychological make-up of the Canadian soldiers themselves. They haven't got anywhere near the same class-structure of the British Army (although officer casualties are making that less and less likely in even that hierarchical bastion) so the idea that they should be relied on to do the individual right thing is striking.

He couldn't have helped but notice even the lance corporals got maps (the Canadians being particularly good at drawing up their own far larger scale ones) and the encouragement for all to use their initiative. This is particularly true now in the more universal acceptance that the platoon was the largest group that could reasonably be commanded by one man in the field. Therefore it shouldn't have grenadiers or machine gunners in support, it should have smaller grenadier groups and machine gunners carrying the new and lighter Lewis gun as actually part of the platoon itself. Can you see how a platoon now becomes its own little army, not a bunch on infantry blokes who need help from other discreet arms of the service?

Onto the 10th itself. They have achieved what they set out to do on the first day, and now the guns have to be brought up. This means two things, apart from a weird atmosphere of calm.

What follows is by way of notes because I don't want to let too much out of the bag for listeners to the episode.

Firstly guns take time, a lot of time, to be repositioned, because guns only have finite ranges and it is a fair bet they were as far back as possible so they could hit their targets but not hopefully be hit themselves. It also takes time if it is being done carefully so some guns remain available to work in defence of our lads in the short term. For Bite and Hold to work, you've got to have this delay so your guns move forward to where they can start Biting again.

Secondly, if you really mean it about Holding, this delay serves as proper time to consolidate. Not turning an MG to face the other way a la Celestine, but building new roads out of stone or logs across No Man's Land (yes, Canadian lumberjacks did this); completely remodelling the German trenches; or in Mickey's case getting his telephone line buried across NML from the point where it emerges from the subway tunnel, and connected to the German telephone network where it goes into their tunnel system. In this way Mickey can lay over a mile of cable, overnight. He's popping down enemy tunnels and dugouts as if they were on his side of the line. (This is all possible because the scouts had used their time and energy to actually learn useful inter-related material.)

What follows is by way of notes because I don't want to let too much out of the bag for listeners to the episode.

Firstly guns take time, a lot of time, to be repositioned, because guns only have finite ranges and it is a fair bet they were as far back as possible so they could hit their targets but not hopefully be hit themselves. It also takes time if it is being done carefully so some guns remain available to work in defence of our lads in the short term. For Bite and Hold to work, you've got to have this delay so your guns move forward to where they can start Biting again.

Secondly, if you really mean it about Holding, this delay serves as proper time to consolidate. Not turning an MG to face the other way a la Celestine, but building new roads out of stone or logs across No Man's Land (yes, Canadian lumberjacks did this); completely remodelling the German trenches; or in Mickey's case getting his telephone line buried across NML from the point where it emerges from the subway tunnel, and connected to the German telephone network where it goes into their tunnel system. In this way Mickey can lay over a mile of cable, overnight. He's popping down enemy tunnels and dugouts as if they were on his side of the line. (This is all possible because the scouts had used their time and energy to actually learn useful inter-related material.)

This process of consolidation began yesterday, and sweeps into the brightly moonlit early hours and through into the 10th. It would be conducted in a feverish calm, if you know what I mean.

The artillery were tasked to call artillery down on a counter-attack at 0400. The guns are available, they've been pre-registered, and they hit and drive off the attack. (We've certainly never been party to such a thing before.)

Dawn breaks and the British can finally see as far as Lens and out over the flat hinterland. Symbolically, the sun comes out over the snowscape. It is virtually empty, with German dots in the distance. This is a consequence of Byng keeping the Germans to their ridge fortifications: there is no deep German killing field behind in this area. Can the Allies convert break-in into breakthrough? Is it stay or go? As the clock ticks, obviously not this time.

They also have the unusual pleasure of being able to see into Vimy, evoking surely the reflection that they have spent two and a half years being similarly overlooked themselves. However, they can't dislodge the snipers in the town, and the British make excellent targets on the ridge against the snow.

Mickey has to call more artillery down on a counter-attack of five thousand Germans coming from Willerval at 1035. He does, and it works again. Now this is more like it.

However, scouts and troops are to go forward in the afternoon to try to take the railway embankment beyond Farbus. This will protect the flank of soldiers advancing on their left to mop up the highest points left over on the topmost end of the ridge, it's vital. A small move here that could protect the backsides of your buddies' miles to the north.

Mickey can use trench mortars and MG's held back to support attacks such as this, thanks to forward planning. No random MG's spraying bullets into the distance as on the Somme. But artillery support from 5th Division is needed. This is where the inevitable organisational tension between keeping guns protecting the troops, and moving guns forward to attack becomes too much and they are unable to support this attack.

To close. After this brisk and efficient start to the Battle of Arras, the subsequent French attack further south collapsed. Haig had no alternative: he had to pour men into his field of battle to support his allies. It was the wrong terrain for anything but Bite and Hold, and he went over to a war of attrition. Arras became on a daily casualty basis (4,076) the worst British campaign of the entire war, surpassing in casualties the bloodbath of the Somme and the mudbath of Passchendaele. Thanks to TOMMIES, it might now be a bit better known.

Obviously I mainly worked with original British War Diaries and unit histories, but do take a look at the Canadian War Diaries which are available online -- and you don't have to pay for them. I think our own National Archives are wonderful, but on this matter many countries have us beat.

VIMY RIDGE AND ARRAS by Peter Barton and Jeremy Banning is one of those books whose clarity of text and extremely useful maps just slots everything into place. Peter also helped me with last-minute enquiries on twitter.

Alexander McKee's VIMY RIDGE tells you the story in a quick pro-Canadian style, and helpfully includes material on the British 13th brigade. More up to date was Brereton Greenhous & Stephen J Harris' CANADA AND THE BATTLE OF VIMY RIDGE.

Beach, Hall and Ferris were of course the main sources for intelligence. Jack Sheldon's THE GERMAN ARMY IN THE SPRING OFFENSIVES 1917 was his normal vital insight into opposition action and thinking.

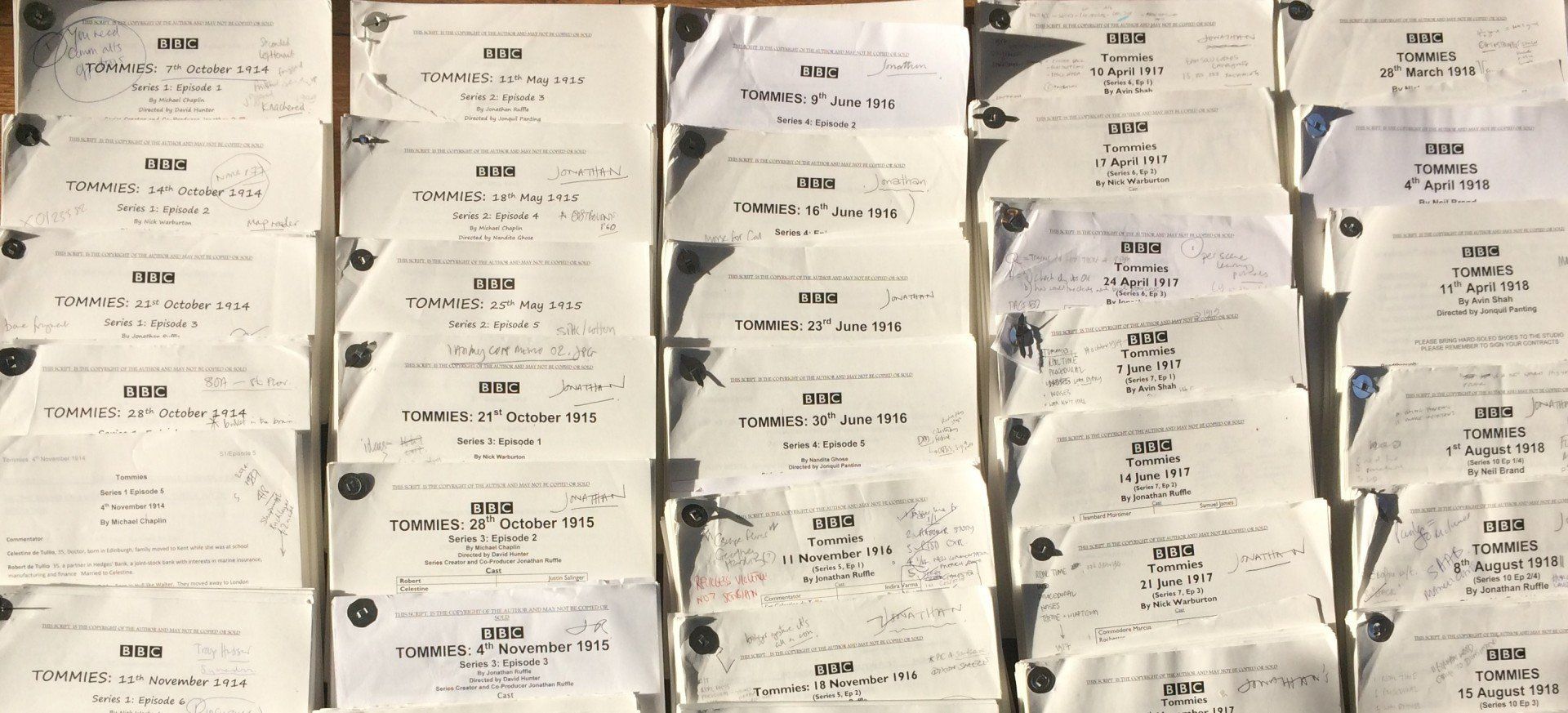

The Imperial War Museum have great Vimy stuff. Particularly good were the private papers of Captain H U S Nisbet of 1 Royal West Kents. This is an amazingly physical collection and I urge you to go to the IWM for a day just to hold and read this incredible material. It includes the actual Continental Daily Mail for 10th April 1917 we featured as well as items he picked up on the battlefield, including German artillery maps. Puts you in the picture indeed.

Both the Canadian and British Official Histories are good, if a little dry.

Related Episodes

Related Episodes